Dear Charlie and Jack,

Happy new year 2025!

For many reasons, mainly my lack of intentionality and structure, I have not written you despite the major goings on in our lives. As you can see, my last letter was posted on June 26, 2021. When Charlie told me sometime last year (2024) that he read all my letters, his grateful enthusiasm for the glimpses provided by the letters into his (and our family’s) early years reminded me to write again. Still, it took me this long, almost a year!, to finally write this. But no psychic self-flagellation for me. I’m back now, at the right place and time. Padayon, as they say in Bisaya. Keep going. Hinay-hinay basta kanunay. Slowly but surely.[1]

I have two reasons for writing you this letter:

First, as the country reels from the unkind and harsh immigration related executive orders and laws passed recently by the new administration, I feel the need to share with you my immigration stories. They’re your stories, too.

Second, because the four people who planned and orchestrated something close to a miracle for our family to immigrate to the US—your Lola Julie and her 3 siblings, Lolo Boy, Lolo Jun, and Lola Genie—have all suddenly passed in the last two years, taking with them their stories…unless we make the effort to remember and record these stories. There will be more letters on them but for now, in the interest of keeping it short and simple, I want to write about the circumstances of my leaving my home.

LEAVING HOME

In December last year (2024), I received the news that Bukidnon State University Laboratory Schools, where I spent my elementary and high school years, awarded me (and several others) the Outstanding Alumni of the Year (for Culture and Arts) award as part of the university’s centennial celebration.

I’ll be honest- I shed tears to know that my high school classmates nominated me for this award. In the midst of my tears, I realized something: I needed this. Not the award- I truly don’t care about the award per se. Rather, I needed the medicine that comes from knowing that one is remembered. I could not have anticipated being gifted this medicine for the wounds I am still trying to heal from leaving my home.

Here is a little bit of my immigration story.

I immigrated to Daly City, California soon after I graduated from high school. Your Lola Julie had left for Los Angeles, your Lolo Bricks followed a year after. They left me, your Tita Ollie, Uncle Eric, and Uncle Erwin with our Lolo Emon and Lola Epang in Malaybalay, Bukidnon. My departure was not planned. In fact, I thought I was going to attend the University of the Philippines-Diliman where I was accepted as a Political Science major. I was really looking forward to living and studying in Manila, the imagined place of sophistication many of us in my high school dreamt of. But my uncle, your Lolo Jun, visited us from the US and took us to an interview at the US consulate. Next thing we knew, we all had H1B-Dependent visas! At first, we were told only your uncles Eric and Erwin were going to the US with Lolo Jun. I’m not sure why, maybe it had to do with them being older. I was 16–the same age as you are now, Charlie!–and your Tita Ollie was 11. Can you imagine how that would have been? Me and Tita Ollie, separated from the rest of the family? Fortunately, it was eventually decided we would all leave.

We had a few days to pack before permanently leaving everything and everyone we knew. There was no time to dispose of our house or our belongings. To this day, I do not know what happened to my personal things I had to leave- my precious trophies, medals, diaries, picture albums, written stories… I was only allowed one backpack. I do not remember what I brought with me. I think I brought fist-sized rocks of tawas (crystal deodorant) because your Lolo Bricks advised there is no tawas in the US.

There was no time for meaningful goodbyes, either. Your uncle Eric threatened to stay—he swore he loved his girlfriend and did not want to leave her. But he was 20 and, well, what was he going to do to support her? Maski saging basta labing wasn’t’ going to work out. (This means: it doesn’t matter if it’s only bananas (to eat), as long as you’re loving.) Your uncle Erwin didn’t return to his second year in nursing school; your Tita Ollie didn’t return to sixth grade. At the despedida party, friends asked me which American university I would attend. Stanford, I answered with conviction. (Ha! How naive I was. I knew so little about how immigration works. More about this- going to college- later.)

When I left, I thought we would never return, even for a visit. I was resigned to the idea that I would never again see our small square of a house with Michael Jackson and Brooke Shields posters on the wall; no longer roam the highway or the foggy capitol grounds or catch dragonflies in the basakan behind our house; no longer hike the mountainous trails and “shower” under the Gantungan falls.

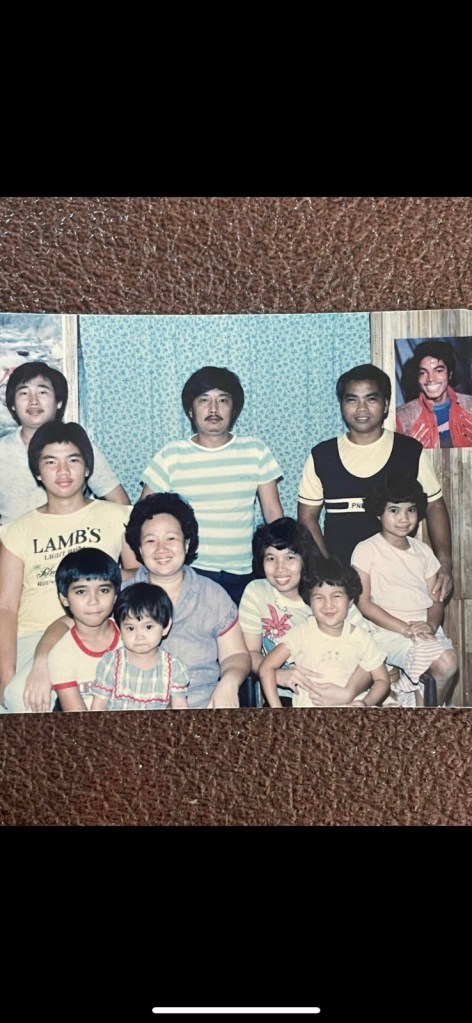

(Family photo: L to R, top to bottom- Lolo Jun, Lolo Boy, Lolo Bricks, Michael Jackson; Uncle Eric, Lola Julie, Lola Genie, me; Uncle Erwin, Ate Hannah, Tita Ollie; circa 1987)

Most of all, I would never again see my friends and cousins, all of whom I grew up with. I predicted all my friends and teachers and the tinderas in the stores where I bought my banana cue snacks would all eventually forget me. “Asa na si Juju?” they would ask. “Oy, wala na sya, she’s gone,” someone would say. It would be just as if I had died.

I was convinced of this because before my family left for the US, several other families did. None of them returned. We remembered them for a while but eventually memories of them faded. Soon, no one spoke about them anymore. That was how it was.

In the late 80s and early 90s, no one could have predicted that the internet and global travel would make separations from ourselves, homeland, and loved ones feel less final and, thus, not so bad. Back then, when we left, we were resigned to the finality of a death-like separation. These days, if and when we leave our homeland and family, the globalized world allows for some reconnection. I take some comfort in this… but still rage at the insidious and complicated reasons for our separation and dispersion from our homeland.

During my first years in the US, I didn’t have time and space to be homesick, especially when my immediate family was with me. Without a US equivalent high school diploma, I went back to junior year in high school and got to live an American teenager life (which was starkly different from what the movies and Sweet Valley High books led me to believe). I bravely carried on as if I didn’t just transplant from one culture to another.

But, hinay-hinay pero kanunay, slowly but surely, the grief caught up with me. It was when I first became a mother to Charlie that I started to realize what I, your ginikanan (a Bisaya word for parent or, more loosely, where you’re from) have lost or forgotten… but now wanted to reclaim and remember so I could pass them on to you–my ancestral languages (Binukid, Bisaya and Tagalog), my ancestral and childhood stories, my immigration stories, my indigenous and ancestral ways of being… To a degree, I’m still reeling from the grief over my death of sorts and grappling with its meaning through the work that I do, writing and publishing stories with the Sawaga River Press. I’m still searching for healing and, in the process, hoping to also offer what I have to those that are trying to also process their grief from leaving their homes.

I understand now that the wound from leaving will never go away, that this wound will continue to shape me and how I act in this world. People like me who are separated from our homeland long to be remembered and claimed by the land and people of our ancestors, even as we try to belong to the land and people where we now live. It is why I publish Bukidnon indigenous stories in the diaspora, why the stories I tell are rife with longing for belonging and wholeness.

When I was told I was nominated and awarded as one of the Outstanding Alumni of the Year awardees, my first thought was- they remember me, after all! I still live in their memories! Daghang salamat, klasmeyts and Bukidnon State University! I hope you know how healing it is for me to know you remember me.

(BSC-SSL Alumni Award Night; my cousin, Dian Villanueva, receiving the award for me)

Charlie and Jack, I write you this to remind you of the power of memory, of remembering. Lola Julie used to remind me (when I regularly misplaced or lost my things), “ang kalimot walay gahum.” Literally, it means amnesia has no power. She wanted me to keep my things. Similarly, I want us to keep our stories. May we remember, slowly but surely, our stories, especially stories about where and who we are from. In these stories is our power.

(Though what I have written in these other spaces–https://www.sawagariverpress.com/blog and https://munganandherlola.wordpress.com/–are not fully about raising you, I want you to see what I have been doing these last few years, shining and thriving while being your mama.)